Author: Mathieu Grandjean

Are humans the future of gender marketing?

Marketing, one of the few areas where the male gender has not always been the focus of attention. And conversely, now that questioning the place of women is at the heart of our society, men are investing in the marketing sphere. Is there a direct correlation between these two trends or is it fortuitous? Lighting attempt.

Homo amarketingus

During the advent of the consumer society and progressively of marketing, it was obvious that there was someone missing, the man.

Indeed, brands for men were specialized, playing on primary needs, experts in their field and marketing only the quality of their product. For example, we think of the famous English tailor Gieves & Hawkes at No. 1 on the no less famous Savile Row Street. Founded in 1771, it is one of the oldest custom sewing companies and they have in particular a Royal Warrants of Appointment, mandates issued to companies that provide goods or services to a royal court or certain royal figures.

The man had a utilitarian logic, he became a customer and remained a customer. Strictly speaking, he was not a target. He often did not even consume himself, often his wife did it for him, or was essentially sensitive to the seller's speech.

Obviously it's a caricature. Some consumer products were reserved for men and he was much more sensitive to marketing concepts that are more common today than he seemed. But the caricature lasted a long time.

Breakdown of family structure and consumption patterns

However, a major change has been taking place in recent years:Man became a buyer and brands have made this half of the population their new fight.

La End of the traditional family unit organized around the working man and the housewife has led to a change in consumption patterns. The older and less stable marriage, the generalization of women's work, have pushed men and women towards greater autonomy.

This societal factor has been accelerated by the awareness of brands of the existence of this new market that is unexplored and to be conquered. The Gender Marketing was born.

Businesses at the human bedside

However, you don't always sell to a man the way you sell to a woman. Thus diet Coca-Cola was perceived as a female product and did not reach the male audience. This is one of the reasons that prompted Coca Cola to launch their Zero range. The black packaging and an advertisement that Stages manhood and action did the rest. Zero became the light of man before being adopted by all and gradually replacing the latter. The topics of the TV ads show it well: for Coke Zero, A man evacuates the apartment of his partner in a helicopter with the Special Troops for not meeting his stepfather in 2009 vs. a group of Young women who fantasize on a gardener's abs for Light in 2013. In 2019, Coca-Zero opened up to a wider population with a spot presenting A retiree who goes back on the road for new, more rock-n-roll adventures.

Brands have therefore redesigned products and communication campaigns. Identity values dear to men are initially taken into account in the presentation and packaging of items, in order to instantly create a strong interaction between the goods and the target consumer. The design And the style code beauty products thus take more masculine forms. Colors and formats generally associated with men are used for product presentation: emergence of blue hues, Black, silver or matt. The use of materials that evoke dominant themes ergonomic, aerodynamics, or even Technological is becoming significant in the packaging of items intended for men.

Finally, it is essential to rename these products on themes and with a language appropriate to speak to humans. Invictus, for example, combining all these best practices: a Warrior name, a packaging of trophy, a Muscular icon who repels his opponents under the crackle of photographers and under the gaze of the gods and five women who await him.

One of the most common illustrations of the upheaval in gender marketing is the growing interest in beauty products. An effective strategy has intensified the need for men to resort to their use. Gender marketing has thus succeeded in familiarizing men with a category of products long considered to be essentially feminine. Cosmetic brands have adapted. They have created specific ranges and new brands. All the marketing capabilities of these major groups have been used to convince men that putting on cream is only feminine anymore! From packaging with “virile” colors and adapted to their uses (with pump bottles rather than jars for example), to Barber Club developed by L'Oréal Men expert, using the numerous tutorials To educate this new target, everything went well.. So much so that today, it seems to have come into fashion and that one of the new trends in cosmetics is unisex!

So who is the marketing man?

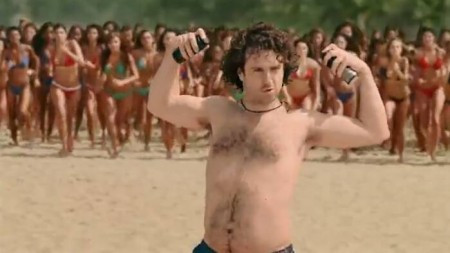

So it is first of all a virile man, competitor, warrior. This is the image of Epinal that the majority of advertisements still convey. Axis going as far as reproducing a scene Mi-koh-lanta mi-300 with the slogan “The more you put on, the more you have” where women come from the land, the mountains and the sea to jump around the neck of a man who wears deo.

The values attached to men are also those of simplicity, energy, success, efficiency. In fact, men's campaigns are often embodied by sports or movie muses.

Nevertheless, we can go further and see that he is a man sensitive to ecology more than to the social, fundamentally gregarious for whom the community is a community of values.

Man as a marketing concept is not yet fully defined. For many sectors, it's changing and it's funny to note that fine segmentations are still quite rare.

Towards unisex marketing?

People have therefore become a target like any other for brands, with their own drivers and their own ways of consuming. Brands have taken advantage of this wealth and while women remain at the top of marketing budgets, men play an ever more important role.

Marketing has since moved some of its energy to unisex marketing that asks other questions.

The movie What Women Want illustrates the vision of femininity by advertisers, who were often male, in the 90s, in the 90s, its male counterpart in the 2010s was not as successful... Was there really no reason to make a movie out of it?

.webp)